Mindful and military: Why mindfulness training is a crucial tool for veterans

“Mindfulness is a universal human capacity — a way of paying attention to the present moment unfolding of experience — that can be cultivated, sustained and integrated into everyday life through in-depth inquiry, fuelled by the ongoing discipline of meditation practice. Its central aim is the relief of suffering and the uncovering of our essential nature.”

( Santorelli, Heal Thy Self, 2010)

After the battle is over, the fighting starts

The mental health needs of military veterans continue to be the focus of numerous research studies and of concern to the general public.

The estimated demand for services varies widely and the impact of these conditions on individuals, which lie behind the statistics, are frequently downplayed by defence departments in their general-purpose communications:

“Fortunately, the rates of conditions like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in our people remain low…” (Ministry of Defence, 2017, p.5).

However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis from Sharp et al (2015), indicates that the prevalence of any mental health disorders in both serving and military veterans is in the region of 37%. Of this group, they report that between 40–60% of these individuals don’t seek help. It is speculated that this is due to the ‘macho’ culture of the military and the stigma of being considered weak if presenting with a mental health issue.

It is reported that of those who do come forward for treatment, 60–70% do not receiving adequate help and that they continue to suffer.

Behind these statistics are the often forgotten families and loved ones who become primary carers for these very troubled individuals and therefore, the overall impact of PTSD, for example, should never be underestimated (Beks, 2016).

The suffering reaches far and wide as family members become at high risk of developing their own mental health issues due to the burden they carry. It was also recommended, many years ago, that they too should receive appropriate interventions (Gaskell, 2005). Two reasons why The Walnut Tree will be unveiling a new, unique ‘affected others’ course in Spring 2018.

Although PTSD is less prevalent in military veterans than other common mental health conditions at 4% vs 19.6% (MacManus et al, 2014), PTSD provides an interesting focus when considering Mindfulness Training (MT), because of the involvement of a range of behavioural symptoms.

For ease of diagnosis these are grouped into four main clusters namely:

- Re-experience

Spontaneous memories of trauma, recurrent dreams associated with trauma, flashbacks, periods of prolonged psychological stress

Area of the brain affected: Hippocampus and Amygdala - Avoidance (of)

Distressing memories, thoughts, feelings, or external reminders of traumatic

events

Area of the brain affected: Hippocampus - Negative cognitions and mood

A range of feelings including a persistent and overwhelming distorted sense of blame of self and others. A significant loss of interest in activities, with estrangement from loved ones and others. Inability to remember key aspects of the traumatic event

Area of the brain affected: Hippocampus and Pre Frontal Cortex (PFC) - Arousal

Displays as aggression, reckless behavioural, sleep disturbance, hypervigilance

Area of the brain affected: Amygdala

There is also a PTSD subtype of disassociation: experiences of feeling detached from mind or body or experiences in which the world seems unreal, dreamlike or distorted.

Area of the brain affected: Hippocampus

(Adapted from American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p.2)

A unique programme providing the help required

The Veterans’ Stabilisation Programme (VSP) is a unique evidence-based programme from Walnut Tree Health and Wellbeing C.I.C in conjunction with Norfolk and Suffolk Foundation NHS Trust. It was conceived by army veteran Luke Woodley, who himself suffered from PTSD, and failed over many years to find appropriate help (NSFT, 2017).

In conjunction with clinical psychologist Roger Kingerlee PhD and John King, a mindfulness practitioner, Woodley, using his lived-experience and extensive research, set about redressing this paradigm for veterans suffering mental ill-health as a result of complex trauma (Kingerlee et al, 2016).

The VSP provides veterans with the discipline and skills to manage everyday life. This cognitive-based group training helps to:

- recognise current mindset and develop skills to change it

- understand the psychology behind PTSD to gain a greater sense of control

- manage and understand difficult thoughts and feelings

- reduce dependence on alcohol and drugs

- improve relationships

- teach the discipline and tools of mindfulness

Mindfulness, when delivered appropriately, is so much more than any of the recent ‘McMindfulness’ pejorative tags. The research literature suggests it can have profound and far-reaching positive effects as indicated by some of the latest research for example; cultivation of compassion for self and others (Khoury et al, 2015), reduction in stress, anxiety and depression (Khoury et al., 2013) and increase in positive moods (Eberth & Sedlmeier, 2012).

Such evidence would suggest that MT has earned its place in the psycho-education of veterans to help them better self-manage their mental health issues (Khusid et al, 2016).

The brain’s most important job and how it is affected by PTSD

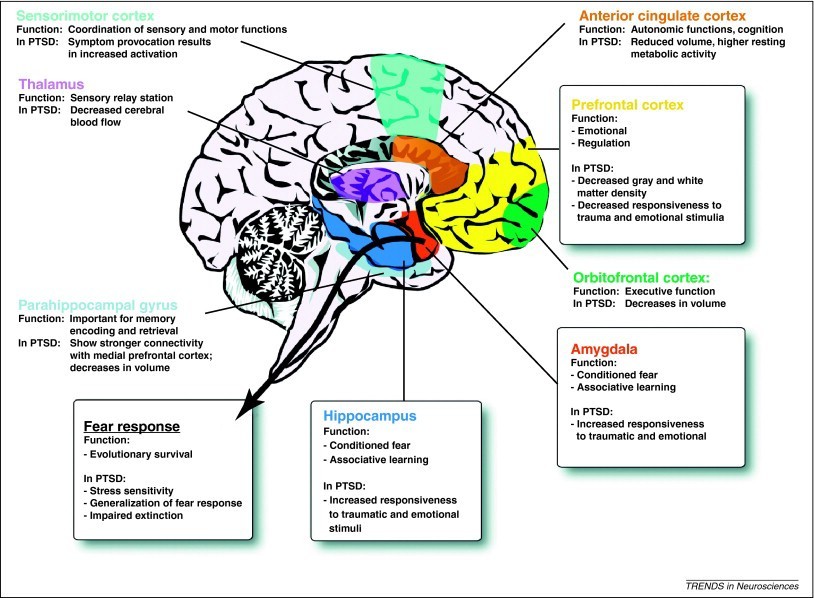

Current research is particularly useful in improving our understanding of what happens to the human brain that is ‘suffering’ the effects of PTSD. The work of Mahan and Ressler (2012), reviews how the neural pathways associated with PTSD in humans is linked to the neural pathways relating to fear.

These pathways belong to the limbic system synonymous with emotional processing. The three brain areas most affected by PTSD are the amygdala, the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex(PFC).

Source: Mahan, A. L and Ressler, K. J., (2012) A schematic of the human brain showing how the limbic system is involved in PTSD. In: Fear conditioning, synaptic plasticity and the amygdala: implications for post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends in Neuroscience

The most important job of the brain is to ensure survival at all costs.

The most important job of the brain is to ensure survival at all costs. To be able to do this effectively it needs to be able to achieve the following:

- signal what the body requires moment to moment eg: food, sleep, sex

- develop a ‘map of the world’ to know where to safely find what will satisfy

- create the appropriate action and energy to get there

- highlight threats and opportunities along the way

- modify actions to suit the current situation

Each structure in the brain works towards one or more of these aims. The primitive, reptilian (bottom) part of the brain is responsible for all the life-sustaining activities of a human being; for example eating, sleeping and breathing. It is responsible for maintaining an internal balance called homeostasis. Any one of these myriad of functions can become unbalanced and cause psychological problems.

Above the primitive brain sits the limbic system which is common to all animals that nurture their young and live together in groups. This is the seat of preferences (likes and dislikes), emotions and the centre of dealing with the rigours of living in complex social settings. The reptilian brain and the limbic system form ‘the emotional brain’. It acts as a welfare officer, looking out for threats and acting accordingly without any reference to the ‘thinking’ part of the brain called the neocortex.

When under a perceived threat, it will automatically run ‘preset’ programmes like the flight, freeze or fight responses. It is in these parts of the brain where the amygdala and hypothalamus can be found (see diagram).

The amygdala acts like the body’s alarm system, monitoring stimuli picked up via the body’s sense organs. If the thalamus has failed to make sense of these sensations, as it does in PTSD, and allows them to become fragmented, the hippocampus, which is responsible for normal memory processing breaks down, causing time to ‘freeze’ giving the impression that the incoming danger will last forever.

The alarm is triggered. Heart rate is increased and blood pressure rises, the body could already be on the move before the rational brain has had time to think. The body is now awash with potent stress hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol. Under normal circumstances, when the threat is over the body returns to a state of homeostasis.

The prefrontal lobes of the neocortex (PFC — top brain), which sits uppermost in the brain, is the site of humans’ ability to reflect, plan, imagine and empathise with others. It is here that the fine edge between impulsive behaviour and acceptable behaviour occurs — this is where choice is made. It plays a ‘command centre’ role. It is the place of discernment. If fear is felt and smoke is detected, this allows for rational thought to occur around is there an immediate danger in the home or has a neighbour just lit a bonfire.

In PTSD, the amygdala is hyper-responsive and the hippocampus and the PFC show reduced activation, the balance has shifted and the symptoms of PTSD start to show. If the balance is to be restored there are two options, work on regulating from the top-down or the bottom-up.

For Bessel Van Der Kolk, one of the world’s leading experts on traumatic stress, “mindfulness… is a cornerstone of recovery from trauma.”

(Der Kolk, 2014, p.96)

If the PFC is to be strengthened (top-down) working with mindfulness to become more aware of the body’s sensations is a good place to start. Formal practices around the body scan and mindful movement can be helpful here (Farb et al, 2007).

Bottom-up regulation via the ‘emotional’ brain can again call upon mindfulness to assist, for example via breathing practices as the breath is both under the influence of both the conscious and autonomic control (Taren et al, 2015).

Christine Forner, a registered clinical social worker with over 17 years of working with complex trauma, takes the importance of mindfulness in the recovery of traumatised individuals one stage further. She postulates that a traumatised brain functions mindlessly or at least is absent of mindfulness. She regards a well functioning medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) as the epitome of mindfulness. This is based, in part, on Siegel’s work The Mindful Brain (2007) around the nine functions of the mPFC:

- body regulation

- attuned communication

- emotional balancing

- response flexibility

- empathy

- insight

- conditioned fear modulation

- intuition

- morality

It appears that Forner doesn’t just want to return her clients to where they were, but sees the opportunity for growth through trauma-informed mindfulness practices. Experience at The Walnut Tree would support this.

“It is knowing how hard it is to become mindful when someone has been dissociating that we can figure out how to help our clients get back on track and find within themselves the place of mindful contentment.”

(Forner, 2017, p.41)

Through an understanding of what is happening in the various areas in the brain when under the influence of PTSD, those who specialise in the alleviation of trauma can begin to align MT appropriately. In short, different mindfulness practices can be targetted to work on the various affected parts of the brain and this should be a major consideration in any design of an MT course.

The VSP does not sit in glorious isolation at Walnut Tree Health and Wellbeing. The organisation has been built on a foundation of mindfulness and compassion for ourselves and others.

Mindfulness meditation is practised by all the directors and there is a non-judgmental and compassionate culture. As the statistics show many of those suffering from trauma will not present unless the environment is perceived as welcoming.

The definition of mindfulness that is used on the course highlights that mindfulness is a skill that can be learnt. It ‘promises’ a way of coping with upcoming experiences. An emphasis is placed on this newfound practice as being a part of daily life, it stresses that it is a discipline — an attitude that is highly understood by military personnel.

It explains the purpose of mindfulness training — the relief of suffering.

Sue Wright an MSc in Mindfulness Studies from the University of Aberdeen. Sue is powered by tea.

Bibliography

AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION (APA), (2013), Post Traumatic Stress DisorderVirginia: APA.

BEKS, T. A., (2016). Walking on Eggshells: The Lived Experience of Partners of Veterans with PTSD. The Qualitative Report, (21)(4), pp. 645–660.

DER KOLK VAN, B., (2014). The Body Keeps The Score. St Ives: Penguin Random House UK.

EBERTH, J. & SEDLMEIER, P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, (3), pp.174–189.

FARB, N. A., SEGAL, Z. V., MAYBERG, H., BEAN, J., MCKEON, D., FATIMA, Z. and ANDERSON, A. K., (2007). Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, (2)(4), pp. 313–322.

FORNER, C.C., (2017). Dissociation, mindfulness and creative meditations. New York: Routledge.

GASKELL, A., (2005). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The Management of PTSD in Adults and Children in Primary and Secondary Care. NICE Clinical Guidelines, (26) (11), [Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56494/.

KHOURY, B., LECOMTE, T., FORTIN, G., MASSE, M., THERIEN, P., BOUCHARD, V., HOFMANN, S. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, (33), pp.763–771.

KHOURY, B., SHARMA, M., RUSH, S., & FOURNIER, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, (78), pp.519–528.

KINGERLEE, R., WOODLEY, L and KING, J., (2016) Developing male-friendly interventions and services. Clinical Psychology Forum, (285), pp.41–47.

MACMANUS, D., JONES, N., WESSELY, S., FEAR, N.T., JONES, E. and GREENBERG, N., (2014) The mental health of the UK Armed Forces in the 21st century: resilience in the face of adversity. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps (0), pp.1–6.

MAHAN, A.L and RESSLER, K. J., (2012) Fear conditioning, synaptic plasticity and the amygdala: implications for post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends in Neurosciences (35)(1), pp.24–35.

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (MOD), (2017), Defence People Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2017–2022 London: OCL.

NORFOLK AND SUFFOLK FOUNDATION NHS TRUST (NSFT), (2017), Veterans’ Stabilisation Programme. Norwich: NSFT.

SANTORELLI, S., (2010). Heal Thy Self: Lessons on Mindfulness in Medicine. New York: Bell Tower (Kindle edition).

SHARP, M., FEAR, N.T., ROMA, R. J., WESSELY, S., GREENBERG, N., JONES, N. and GOODWIN, L., (2015) Stigma as a Barrier to Seeking Health Care Among Military Personnel With Mental Health Problems, Epidemiologic Reviews, 37(1), pp.144–162.

SIEGAL, D. J., (2007). The Mindful Brain in Human Development: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-being. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

TAREN, A. A., GIANAROS, P. J., GRECO, C. M., LINDSAY, E. K., FAIRGRIEVE, A., BROWN, K. W., ROSEN, R. K., FERRIS, J. L., JULSON, E., MARSLAND, A. L., BURSLEY, J. K., RAMSBURG, and CRESWELL, J. D., (2015). Mindfulness meditation training alters stress-related amygdala resting-state functional connectivity: a randomized controlled trial. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, (10)(12), pp. 1758–1768.